|

|

Post by cromagnonman on Mar 5, 2016 22:23:42 GMT

It is a truth - albeit one not universally accepted (and what sort of megalomaniacal egotist presumes to speak for the universe anyway?) - that all good literary ideas result in three distinct consequences. The first is slavish imitation. The second: strained attempts at variation. The third: genuine innovation. Nowhere is this dictum better demonstrated than in the history of sword and sorcery fiction over the twenty year period beginning in 1966.

In the wake of the success enjoyed in that year by a resurrected Conan in paperback it seemed for a time as if every second string publishing imprint was intent upon clambering aboard the barbarian bandwagon. Characters both old and new were conscripted to the cause of competition with varying degrees of success. Some, like Norvell Page's Prester John, brooked worthy comparison with Howard's magnificent archetype. Others, such as John Jakes's bland facsimile Brak, did not.

After the initial torrent of beefcake books and hackwork had run its course ever more desperate novelties were deemed to be needed to maintain impetus and interest in the material. This glib mode of reasoning would ultimately culminate in the self-parodying dregs of David Jarrett's WITHERWING and C M Gilbert's Chael of the Steel Fist. (Curiously the comics industry which experienced its own identical challenge in the mid 1970s, when faced with the runaway success of Marvel's Conan comic-books and magazines, reacted with far greater flair and imagination. DC's Claw the Unconquered and Stalker, and Atlas's kitsch classic Iron-Jaw, were inventive and entertaining attempts at variation on the barbarian hero template, but - regrettably - no more commercially successful).

It was only from the mid 1970s onwards when a new generation of young fantasy writer emerged - one steeped in the lore of the 60s publishing glut and so well equipped to discriminate between what was good and what was bad in sword and sorcery, and talented enough to elaborate upon the former - that genuine creativity began to be injected once more into the moribund formula. Publishing first in the small press before gravitating into paperbacks a conveyer belt of fresh and original talent began producing some of the most exciting developments seen in sword and sorcery since the heyday of the pulps: writers such as Richard Tierney, David C Smith, Adrian Cole, Charles Saunders and the tragic David Madison. In the process they succeeded in establishing the last pantheon of great fantasy heroes: Simon of Gitta, Oron, the Voidal, the mighty Imaro and the quirky Marcus & Diana. It was a process that reached its apotheosis with the advent of the immortal Gemmell and the watershed in fantasy marked by the publication of his classic LEGEND in 1984.

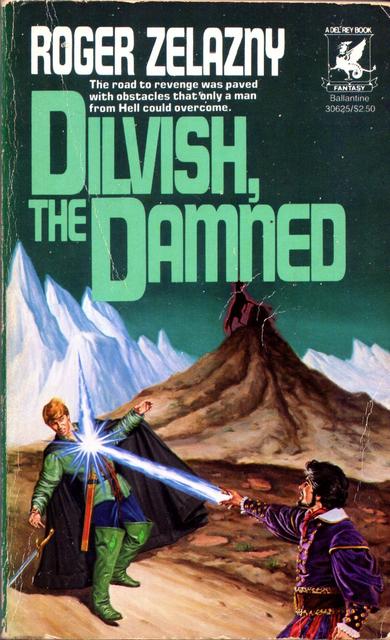

It goes without saying that there are exceptions to every rule which prove them to be true. Roger Zelazny's Dilvish the Damned - the subject for particular discussion here (in case you were wondering if I'd forgotten) - being a case in point.

Along with Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd & Grey Mouser and Mike Moorcock's Elric Dilvish is one of only four s&s characters (three if you count Fafhrd and the Mouser as a composite) to have been created prior to the Conan boom of 1966, to have weathered the ensuing slough of imitative hackwork and to have re-emerged in the 1980s still being written about by the original author.

Zelazny, like his contemporary Poul Anderson, is a writer whom I guess most people would more usually associate with the raft of multi award winning science fiction he produced over the course of a long career. The fact is that the both of them started out as dyed-in-the-wool fantasy writers. Whereas Anderson would only return intermittently to the genre after contributing the superlative defeating BROKEN SWORD (one of the two best s&s novels ever writtern) Zelazny's fantasy cv is more extensive. Mostly this is on account of the classic ten volume Chronicles of Amber sequence, but there are outstanding fantasy standalones to his credit too such as JACK OF SHADOWS and TO DIE IN ITALBAR.

Dilvish was the hero of Zelazny's first professional forays into fantasy, beginning with "Passage to Dilfar" in the February 1965 issue of Fantastic. This was a time when the magazine was in the throes of losing its great female editor Cele Goldsmith who had made Fantastic a rare repository for new tales of s&s during a dark period for the genre. When Goldsmith departed in the summer of that year the genre lost its most astute and capable patron, and Zelazny's nascent hero along with her. A couple of fleeting appearances notwithstanding over the intervening years it was not until 1979 that Dilvish resurfaced in earnest.

It was against the backdrop of a mini revival for s&s short stories, occasioned by such brilliant showcases for them as Andy Offutt's SWORDS AGAINST DARKNESS anthologies, that Zelazny was persuaded to resurrect Dilvish. New adventures were commissioned for such diverse outlets as Stuart Schiff's Whispers and Lin Carter's FLASHING SWORDS series. Evidently encouraged by the response to these efforts Zelazny surprised everyone with the subsequent completion of a full length Dilvish novel. This was THE CHANGING LAND which was published by Ballantine in 1981. The following year he returned to the original short stories and attempted to weld them together into a single cohesive narrative by the addition of several specially written new tales. This portmanteau novel - of the type that Keith Roberts used to specialise in - was published by Ballantine in November 1982.

Zelazny was later to claim that it had always been his intention to link the stories in this manner, and that the original idea had been to publish the result under the title NINE BLACK DOVES. Speaking from a purely personal perspective I find it hard to give too much credence to this notion. The nine black doves themselves "that must circle the world forever, never to land, seeing all things on the earth and on the sea, and passing all things by" are a conceit in keeping with others in the book such as the relief of Dilfar and Selar's invisible sword, one casually forgotten when proved inconvenient. Lapses of this sort lead me to question how much effort Zelazny really put into rationalising all the material he collected into this book. Material which, it must be reiterated, was originally crafted intermittently over a fifteen year period.

But whatever failings it may exhibit as a novel should in no way be confused with a failure as a book. Quite the contrary. Because DILVISH, THE DAMNED is a quite brilliant collection of highly imaginative, witty and exciting adventures. And Dilvish himself an engaging, intelligent and capable hero to experience them with.

The story entitled "Thelinde's Song" provides most of the requisite background information concerning him. Dilvish is the hero of an old war; a man with elvish blood who earned himself the title of "Deliverer" for having saved the besieged city of Portaroy. In the days following the battle, and basking in his newly won status, he encounters the sorcerer Jelerak in the process of offering up a human sacrifice. Rushing to intervene - in old school heroic fashion - Dilvish is disconcerted to find his body perfunctorily turned to stone by the sorcerer and his soul consigned to Hell where it endures unremitting torment at the claws of the demon Cal-Den. Two hundred years pass and Dilvish is unceremoniously repatriated to earth when the city of Portaroy once again comes under attack. He returns thirsting for revenge against Jelerak. And he comes armed with a collection of spells known as "Awful Sayings" which have the power to level an entire city. More importantly he is accompanied by a demonic familar called Black which takes the form of a huge metal horse. Black is a fantastic character in his own right. He breathes fire, pulverises stone walls (and men) and his sardonic observations provide some of the chief joys of the book.

DILVISH, THE DAMNED consists of eleven stories of varying length. They run the gamut from brief vignettes to full length novelettes. Inevitably a couple of the tales underwhelm, but for the most part this is sword and sorcery of the very highest calibre: clever, inventive, often funny and wonderfully entertaining.

This is not a book which wades ankle deep in its own gore as do those by Howard and Wagner (or waist high in excrement like those by Abercrombie). It has its own captivating quality and should be considered an essential volume by anyone with a love for the genre.

|

|