|

|

Post by Steve on Feb 5, 2008 14:32:33 GMT

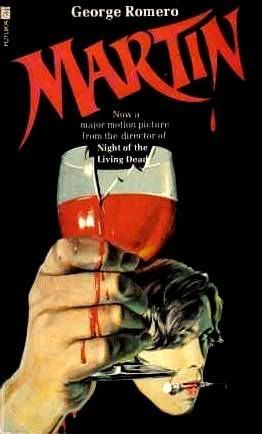

Futura, 1978 (orig. Stein & Day, New York, 1977) Futura, 1978 (orig. Stein & Day, New York, 1977)Martin was young and good-looking, a shy boy, perhaps even a little backward. But Martin had a secret, one he couldn't share.

His uncle knew the family had brought the poison with them from the Old Country. He was waiting for the day he could destroy Martin and Martin's evil.

Others knew - a woman Martin had met on a train, a woman he'd followed from a supermarket. But they were dead...

A Chilling story of an ancient evil unleashed on a modern city. Following on from Sean's recent posts on Night of the Living Dead & Dawn of the Dead, here's a third George Romero tie-in. For my money, Martin is the best thing Romero's ever done - the story, in case anyone's not seen it, of a very disturbed and deeply confused young man, a serial killer, who believes himself to be an 84 year-old vampire. The blurb on the back of the book hints at supernatural goings on, but Martin's 'fangs' are razor blades and syringes and the story deals with the young protagonist's internal struggles and the differing reactions of those around him - his elderly uncle, would-be vampire hunter Tati Cuda, who seeks to destroy Martin; and Cuda's grand-daughter, Christina (played in the film by Romero's wife, Christine Forrest) who attempts to understand him. Romero gets sole writer's credit on the cover of this UK edition from Futura, but further investigation (i.e. the title page) reveals that, as with Dawn of the Dead, Susanna Sparrow shared the writing duties - presumably 'novelizing' Romero's original script. All Romero's own work is the interesting afterword, in which he explains something about his reasons for making Martin. The element of social commentary in George Romero's films is often mentioned - an obvious example being Dawn of the Dead's satirising of consumer society - and he makes it clear here that Martin should be viewed as an allegorical work, a parable. He suggests that the vampire is one of the most sympathetic of monsters (actor John Amplas conveys this beautifully in the film). He possesses a certain charm, an attraction, and is ultimately as much a victim of his curse as those he preys on. This mix of monstrosity and vulnerability make him the ideal "mythical whipping boy" for society to hunt down mercilessly and brutally punish as a way of absolving our own primal sins and desires. Is the vampire really any more monstrous than the angry, baying, pitchfork wielding mob? It's this response that Romero views as 'the heart of the matter' - our eagerness to judge and destroy that which we feel threatened by, without seeking first to understand it and consider what this 'horror' might reveal to us about ourselves - "Not only are moral lines difficult to draw, but any attempt to broadly categorize behaviour as good or evil will warp any true search for the nature of man." He draws parallels with a number of other 'monsters' from life and legend; Dracula of course (he mentions Raymond McNally & Radu Florescu a couple of times, and their In Search of Dracula, as well as McNally's A Clutch of Vampires - which he refers to specifically - seem to have been two of his references when making the film), Sawney Beane, the 'Manson Family', and then contemporary serial killers like The Los Angeles Slasher. Again it's our reactions to these figures - the real-life monsters no less legendary than the fictional ones - that concern Romero; "Are there those among us in... 'normal' society who would today take pleasure from driving a stake through the L.A. Slasher's heart?" Monsters are real, he points out. They exist - "in us and among us" - but to merely demonise them is evading the issue, and dangerously so; "If he is our own child, if he is our primal conscience looking back at us from the center of our souls, then Martin is truly a dangerous creature, for then he has us all figured out, while we haven't come close to understanding him." Thanks to jerrylad for this one! |

|