It is no accident that the majority of the most prominent and important players in the fanzine culture of the 1970s were all Canadian, or at least Canada resident. As previously stated Gene Day was the pivotal figure in the culture and his gravitational influence drew a number of talented and like-minded artists into orbit around him. There was Charles Saunders most obviously, but also Galad Elflandsson, Dave Sim, John Bell, Charles de Lint and John Charette. Sometime in 1977 the simple fact of this proximity of available talent lead a group of them to set up the Triskell Press which aimed to issue a range of semi-prozines devoted to various strands of fantasy. The first product of the endeavour was

Dragonbane.

Artwork by John Charette

In terms of pure aesthetics I don't think the culture ever produced a more handsome looking title. With the singular exception of the last two issues of John Martin's

Anduril. Dragonbane was magazine sized, and professionally printed on quality paper which afforded excellent reproduction to its fabulous artwork

. Its intentions were just as admirable in wanting to be "a showpiece for the best in new fantasy fiction" and in pursuit of that aim it assembled an impressive roster for what was to prove sadly its sole outing: Tanith Lee (still new enough on the block at the time to qualify for inclusion in a semi-prozine), Elflandsson, David Madison, as well as editor Charles Saunders and publisher/proprietor de Lint. If names and admirable motives alone were all that was needed to guarantee success then

Dragonbane would have been a publishing triumph. Sadly it takes a bit more than that. Good storytelling for a start and on that score publisher de Lint's truly wretched effort of sword & sorcery rather undermined the ethos of the undertaking.

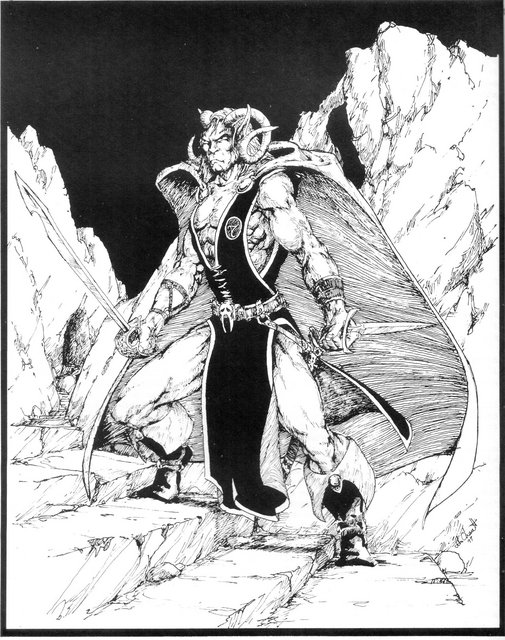

Artwork by John Charette

Critics of sword and sorcery dismiss the writing of it as something absurdly simple. What could be more straightforward than the setting of a meat headed muscleman against a magician or a monster. But sword and sorcery is no easier to write than any other sort of genre fiction and is actually more problematic than some. The hero presents a particular challenge. He or she obviously needs to be physically elevated above the average. But exaggerate their strength or resiliance too much and they become indestructable cartoons. It is a fine line that is drawn between impressive displays of strength and superheroics. One of the enduring qualities of Robert E Howard's writing is that he seldom put a foot wrong in this distinction. Unlike De Camp who saw nothing implausible in having Conan wave marble benches above his head.

Equally a sword and sorcery story must feature a degree of realism. Because if this is omitted then there is no yardstick against which to measure the hero's feats and the story is consequently drained of drama. A hero without constraints set upon them can never be truly imperiled and therefore draws no emotional investment.

I offer these observations as an insight into the woeful failings of "Wings Over Antar" which, in my estimation, offers a textbook example of how

not to write sword and sorcery. Because in flouting both the above rules (and several others beside) de Lint produced one of the most awful stories of the sort imaginable.

Artwork by John Charette

Let's start with the hero, Damon the demonspawn, superbly rendered in the above drawing by John Charette.

In a preposterous info dump of a prologue we are informed that Damon actually started out as Daelin Wood-wise, the happy elf. But after his elven family are massacred by the minions of Noth Seganth - for unexplained reasons but then the sorcerers of this story need no motivation other than their own foulness - Damon renounced his heritage in a pact with the Nether Gods in exchange for the powers necessary to avenge his family.

So we have a hero with strength many times that of the average man, with wicked horns curling around his head. Moreover he is possessed of an - implicitly - magic sword and he rides a unicorn called Storm-strider. And yet when he walks into the obligatory tavern for a drink no one bats an eyelid. There are no calls of "Anyone here got a unicorn parked outside?"

But even with all these resources at his disposal he still manages to get himself crucified to a rock. Yes, that's right; a rock. Frankly I think the soldiers who achieved this feat in the desert in the dead of night without smashing every bone in Damon's hands and feet are more to be complimented here than our intrepid hero. But Damon is so tough that not only does he manage to wrench himself free by sheer brute strength but he actually kills half a dozen winged bird-beasts that are attacking him

at the same time.

This quite risible sequence is an obvious riff on the famous instance of the crucified Conan in "A Witch Shall Be Born". But it is so ludicrously over the top that it reads like a spoof. Conan's killing of the vulture with his teeth was designed to be the ultimate testament to his incredible vitality and fortitude. But even he wasn't able to extricate himself from the cross unaided and it took him months to recover from the ordeal. Not only does Damon free himself but he's off climbing castle walls and engaging in pitched battles with guardsmen

the selfsame night.

The list of absurdities goes on and on. Winged women have clandestine meetings with their informants in taverns where everyone can see them. Damon penetrates a castle keep by jumping over the wall [de Lint had clearly never seen a castle keep at the time or possessed the slightest knowledge of fortifications]. Damon manages to both hurl a spear and throw a sword simultaneously (which is physically impossible) and impale guardsmen with both weapons.

I could continue but you get the idea. All things considered its godawful drivel. But if this was the publisher's notion of what constituted "the best in new fantasy" then what is to be made of the remainder of the contents?

A question to be considered shortly.

![]()