|

|

Post by cromagnonman on Oct 16, 2018 21:57:35 GMT

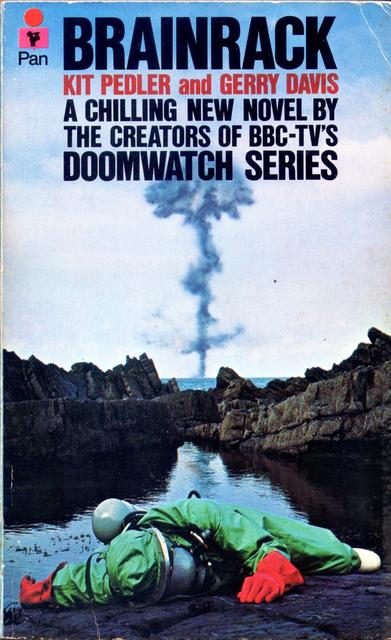

Here is a book which, on the face of it, would seem to be one which Time is not going to have been very kind to. Few stories date more rapidly than cautionary environmental techno thrillers and with this one having been published as far back as 1974 there is every reason for expecting it to read as quaintly to the modern eye as the most hopelessly optomistic SF of the 1920s. And to begin with such a jaundiced view would appear to be justified as the book postulates some bizarre notions which have quite clearly not been borne out by the passing years. But persevere beyond these initial jarring notions and you are rewarded with some quite startling prophecies which strike a grim resonance with the headlines of today. The book begins with the switch over to a new air traffic control system which almost immediately results in a narrowly avoided mid air collision. The hero of the book, Dr Alexander Mawn, uses the incident to publically criticize the technology involved which has been supplied by the Gelder Consortium. Mawn is one of those irascible hard drinking maverick scientists found so commonly in stories of this type, but given a degree of additional plausibility in this instance on account of clearly owing something to co-author Pedler who, by all accounts, was something of a maverick scientist himself. In no time at all Mawn's laboratory is a target for industrial espionage which results in the facility being inadvertantly destroyed and one of his assistants killed. And from this point on the book adopts something of a polemical tone as Mawn struggles to prove his theories relating to the inherent untrustworthiness of technology. One of Mawn's big ideas - namely that the more sophisticated technology gets so the more inefficent it becomes - isn't one that really fits the facts as we know them. Though I'm sure Scotty from Star Trek would have raised a tumbler to the notion: "the more they overtake the plumbing the easier it is to stop up the drain". Mawn's efforts bring him into contact both with Sheldon Peters, a tv journalist looking to use Mawn's notoriety to revitalise his own career, and Marcia Scott, an American clinical psychologist who sees parallels in Mawn's theses with her own research. Scott's work is actually far more expansive than Mawn's and has succeeded in proving that groups of test subjects working in technological capacities are suffering pronounced and irreversible deteriorations in intelligence. The social and economic implications of this discovery are truly staggering and the discussion of them accounts for a fair number of openly didactic passages. Scott's research is given frightening urgency by the fact that a number of her tested subjects are employed in the new nuclear power station being constructed by the Gelder Consortium at Grim-Ness in the Orkney Islands. When Mawn and Scott fail to persuade the government to delay the start up of the reactor they find themselves on site when all their dire predictions are realised and the atomic core goes into meltdown. It is at this point that a stimulating exercise in polemics suddenly morphs into a first rate thriller. Mawn's efforts to evacuate a group of survivors from the heavily irradiated ruins of the stricken plant make for edge-of-the-seat reading and are brilliantly convincing. Coming a full five years before the self-same incident at Three Mile Island and twelve years before Chernobyl the authors' warnings on the dangers of nuclear power are commendably astute although hardly unprecedented given the example of the Windscale fire of 1957. Where Pedler and Davis really do achieve a triumph of prescience is in the identification of the agent responsible for the mental retardation, or what the media come to dub the Brainrack effect. I wont spoil the enjoyment of any prospective reader by identifying it but suffice to say it is an issue which is making headlines even now. This is a fact which serves as a testament to the authors' foresight but is also a damning indictment both of the self-interest of industrial big business and government inaction and a salutary commentary too on the reluctance of society to accept profound reforms to modern living. This is a powerful and thought provoking work which rewards every moment spent in reading it. It has plenty to offer by way of critical insight into 21st century life despite being written more than four decades ago. Mawn may be misplaced in his contention that the mere process of interacting with technology is making idiots out of modern man, but in a world where people lurch though the streets like zombies absorbed in their mobiles and plough their vehicles over cliffs and into rivers because their satnavs tell them to can anyone seriously doubt the dangers he identifies of humanity becoming an unquestioning slave to its own technology? |

|

|

|

Post by killercrab on Oct 17, 2018 7:55:02 GMT

I’ve read Pedler & Davis’ ‘Dynostar Menace’ and remember that was equally gripping. Thanks for the write up.

KC

|

|